Mixed History Can cocktails serve up more than booze?

By Osayi Endolyn

On February 1 of this year, Saint Leo, an Italian-inspired restaurant in Oxford, Mississippi, introduced five drinks to its seasonal menu. The heading read BLACK HISTORY MONTH COCKTAILS FEBRUARY 2018 BY JOE STINCHCOMB. Informed enthusiasts might have read what followed as a curious and challenging lineup. But then, generally speaking, most diners aren’t informed enthusiasts.

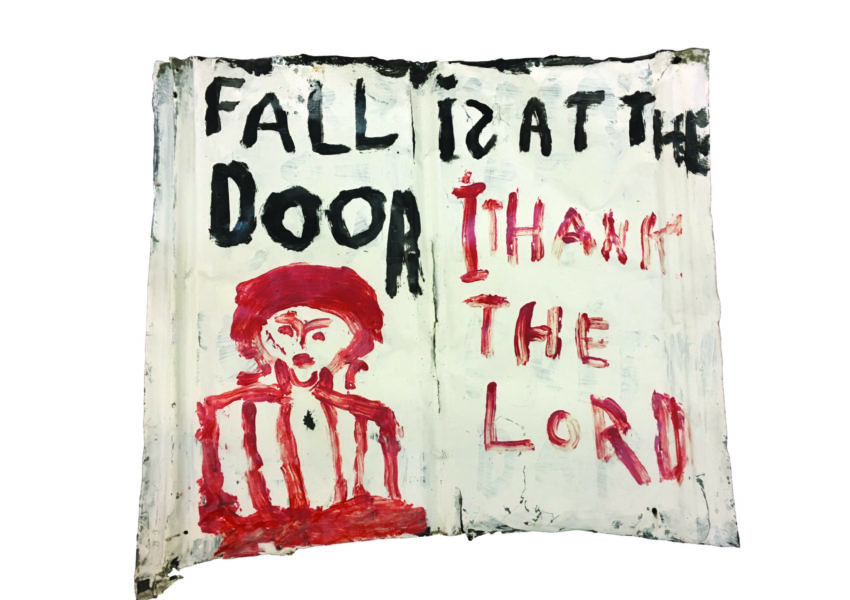

![]()

Blood on the Leaves, a Mai Tai twist, featured St. Croix rum and pecan orgeat. Bullock & Dabney was a mash-up of the Corpse Reviver and Mint Julep, flushed with bourbon, Bénédictine, rhubarb, and citrus. The Clyde began with blanco tequila, mellowed by pinot noir, and floral rooibos tea. (I’m Not Your) Negroni riffed on the classic, boasting gin infused with West African grains of paradise. Black Wall Street blended the Black Manhattan and Whiskey Sour with bourbon, amaro, lemon, and a wine float.

Eleven days later, after Saint Leo received multiple calls threatening protest, owner Emily Blount and Stinchcomb, the restaurant’s beverage director, pulled the special cocktail menu. A bar guest had posted an image of the menu on Snapchat; others posted to Facebook. People were offended. Observers wondered who wrote the menu and what was meant by it. The comments were swift. How could they? Whose idea was this? Boycott! Blount and Stinchcomb surveyed the sudden change of events. How did this happen? The Black History Month menu had seemed like a good idea.

Stinchcomb, twenty-eight years old, is a passionate man. His words tumble into each other; his bespectacled eyes brighten when he talks. He grew up an Air Force brat, and spent time in Germany, Croatia, Colorado Springs. For a time, he lived in Fayetteville, Georgia, where his father had been born. His grandfather, for whom he is named, was a Montford Point Marine, one of the all-black recruitment group that integrated the Corps in the early 1940s.

After Stinchcomb graduated from the University of Mississippi in 2013, he took up bartending. Blount hired him when the restaurant opened, after he’d honed skills at the high-volume Proud Larry’s (and geeked out on liqueurs and infusions at home).

His bar program is one of many bright spots at Saint Leo, named a 2017 Best New Restaurant semifinalist by the James Beard Foundation. They grew popular serving wood-fired pizzas—the burrata and soppressata with chili flakes is my standing order when I’m in town.

Early on, I fell for Stinchcomb’s Golden Rule, made with blanco tequila, yellow Chartreuse and dry Curaçao. The Grown Simba, an early drink, referenced a song by rapper J. Cole. If you were in on the head nod, snaps to you. If you liked the flip-style drink—gin, sweet and dry vermouths, orange juice, egg yolk, and grated nutmeg—great. If you inquired about the name so Stinchcomb could nerdily quote lyrics as he’s apt to do, all the better.

He’s dropped a hip-hop or pop-culture drink reference on every seasonal menu since the first day of service. Almost two years into his tenure, he took the next step. Joe Stinchcomb presented a portrait of America as seen through the eyes of a black man.

Stinchcomb had studied Louisville-native Tom Bullock’s The Ideal Bartender, the first cocktail recipe book published by an African American. He’d read W.E.B. Du Bois’ 1903 classic tome The Souls of Black Folk, an underread masterpiece. Stinchcomb was especially taken with Du Bois’ term “double consciousness.” He understood the idea of dividing his identity on the basis of race, as a black man in a service role in a predominantly white Mississippi restaurant. He’d been inspired to think of his role as an African American bartender in the South as more than a job. He saw his work as a continuation of a rich cultural legacy. He’d recently attended BevCon in Charleston, where he heard historian David Wondrich and bartender Duane Sylvestre present on underreported drinks history. Stinchcomb aimed to use his station at Saint Leo, which borders the Courthouse Square in Oxford, to acknowledge and celebrate African American heritage in all its complexities. He developed this menu, which he taught to a receptive and curious staff, to highlight the achievement, struggle, and sacrifice of black people in the United States. He hoped it would encourage all people to sit up, sip slowly, and reflect.

“I wanted people to feel how I feel as a black person in America. I didn’t get a blueprint on this. I wasn’t told how to navigate these waters.”

Through snapshots of the menu and paraphrased status updates on Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat, Saint Leo’s Black History Month cocktail menu received more eyes on it than Stinchcomb had anticipated. Some of the most vocal critics were liberal arts faculty at the University of Mississippi. The cocktail menu had no glossary, summary, or additional context, leaving intention open to interpretation. Online, people couldn’t discern that the menu author was a black man—and when they found out, it just complicated the narrative. Stinchcomb admits a written statement might have been useful, but he had his reasons for leaving one out.

“I wanted people to feel how I feel as a black person in America,” Stinchcomb said. “I didn’t get a blueprint on this. I wasn’t told how to navigate these waters.” Those waters run deep: White patrons sometimes call him “boy” to get his attention. He is a rare black bartender on the Square in a town where many black laborers work in food service. There’s the psychic stress of seeing people who look like you constantly hauled off and communally policed for golfing slowly, for behaving age appropriately in grade school, for waiting on friends at Starbucks, or for pushing one’s infant in a stroller in a public park—in daylight. “I wanted people to think, ‘why do I have this awkward feeling, this discomfort?’”

For some black people, their shock was formed by the first drink on the menu, Blood on the Leaves. It references Billie Holiday’s 1939 haunting classic, Strange Fruit, which confronts the legacy of lynching in America. With the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, we have just begun to do the necessary societal work to heal from this terrorism.

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Stinchcomb used rum to evoke the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean. Blood orange symbolized the exoticism of blackness. It is constantly desired, for example, in sports—but also forbidden. He chose pecans to make orgeat in place of almonds because pecans are native to the South. Stinchcomb told me that a university instructor said the drink commodified black pain and suffering.

(I’m Not Your) Negroni rankled, too. Stiff and complex, the drink relies on a cherry-infused Campari that rounds out the peppery cardamom of the grains of paradise. Thematically, Stinchcomb was referencing the Raoul Peck film I Am Not Your Negro, a 2016 documentary based on James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript. Some black people were disturbed by the play on “Negro”—some later admitted they didn’t realize Negroni was also the name of an Italian cocktail, which, given the context of the beverage menu, might seem obvious. But it underscores how quickly emotions around race can blind us to closer reads. Stinchcomb says they missed the point. “I was hoping people would focus on ‘your.’ Baldwin was saying, ‘I’m free! I’m my own person!’ The focus was not ‘Negro.’”

Negro can be fraught, despite its ongoing use in black vernacular among select company. Some of this is cultural, and some is generational. New Orleans chef Leah Chase recently told me, unrelated to this incident, that she preferred the term. In her day, she said, they were just colored. “But anyone could be ‘colored,’” she told me. “At least with Negro, it felt like something.”

For others, the most objectionable drink was Black Wall Street, which references the early-twentieth-century black community in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma. (It was once called Negro Wall Street.) Black Wall Street was one of the most notable and successful examples of African American–led business districts in the country, replete with physicians, realtors, lawyers, and other fixtures of a vibrant, upward-bound economy. But, as the elders say, we can’t have nothin’. Between May 31 and June 1, 1921, police and Tulsa national guardsmen, with help from neighboring white residents, razed the neighborhood. Black businesses and homes were looted and burned. Hundreds of people were killed. Thousands were rendered homeless. It’s still sometimes called a “race riot,” but it was an envy-fueled massacre. Colson Whitehead’s most recent novel, The Underground Railroad, features a scene that mimics this devastating event.

A common complaint about the menu and its uncomfortable references was that people don’t go to bars to learn about mass murder. No one wants racial animosity with their $10 cocktail, some argued. But Stinchcomb hoped the drink would spark awareness in the pride and ingenuity that preceded the bitter end to Black Wall Street. Why does black achievement vex so many white people? Stinchcomb leaned back in his chair, reflecting on the drink and why it conjured so much anger. “It’s big, it’s black, and it’s rich.”

By way of the Bullock & Dabney drink, Stinchcomb aimed to introduce guests to Tom Bullock and John Dabney. A veteran of the St. Louis Country Club in Missouri, Bullock published his drinks manual in 1917. Dabney, born enslaved in Richmond, Virginia, was a celebrated caterer and social figure. A master bartender known for his Mint Juleps, he used his bartending tips, which his owner allowed him to keep, to secure his wife’s freedom, his mother’s, and finally his own. That’s a hell of a lot of drinks. And it’s a nod to the double-edged role that tipped wages played during slavery—and still play now.

The Clyde is named for Clyde Goolsby, who owned the Prince Albert Lounge at the Oxford Holiday Inn. In the 1980s, Goolsby was famous for his Singapore Slings and margaritas. “I had to pay homage to the trendsetter in this town for me,” Stinchcomb says. The pinot noir in the Bullock & Dabney pairs beautifully with the rooibos, lime, and bitters. Stinchcomb identifies with Goolsby and what he must have overcome to own a bar in town. In Willie Morris’ essay collection Shifting Interludes, an unnamed customer describes his relationship to Goolsby in a piece called “Coming on Back.”

I don’t quite know how to say this,” a white merchant tells me, “because I’m an old country boy and I grew up the way it was down here, but Clyde’s my best friend in the whole world. Damn, I love Clyde! So does everybody else, coloreds and whites. What would this town be without him? If we didn’t like the ol’ mayor so much, we’d run Clyde. Hell, still may.”

We’re primed to note matters of race and privilege like these. And we should. In 2015 at a Berkeley, California café, wait staff “shooed” comedian W. Kamau Bell from talking to a white woman holding a baby, and her friends. He wrote about it, the post went viral, and the business was soundly critcized. Bell is a black man who had just dined at the restaurant; the white woman was his wife, the baby their child. Citing a failure to rebound from the bad press, the café closed this past April. Bell had initially received widespread support, but he says some of those supporters, many of them white, now blame him for the closure.

From my computer screen, Saint Leo’s harshest critics seemed to be people who had never been to the restaurant; a number of them appeared never to have visited Oxford. Stinchcomb said black people told him that his menu couldn’t have any positive impact in a town like this-. “Maybe Memphis or Jackson. Maybe Brooklyn. Not in Oxford,” he recounted. People said he should have hosted a dinner, a pop-up, maybe off-site and away from Saint Leo and the Square, where he could present his themed menu.

Others questioned his background. In the hubbub, a black writer friend from this region argued that Stinchcomb’s menu and my openness to it were a result of our not being born and raised in the South (I’m from California). She felt that being black and from the South afforded her an inherent knowing of the limits between black and white people. Blackness in America has always been judged by degrees, but I’ve never considered regionalism as a mitigating factor of black identity. A few days after pulling the menu, Stinchcomb reinstated Bullock & Dabney and The Clyde. The drinks were celebratory and broadly perceived as noncontroversial. And, he felt, they were damn good recipes.

If food and beverage is the cultural laboratory we’re saying it can be, then why do we struggle with the idea that drinks can serve as a text for complex ideas? We give music, art, and television plenty of leeway. Trumpeter and composer Wynton Marsalis’ 1997 epic, Blood on the Fields, dealt with America’s history of genocide and enslavement. The piece earned him a Pulitzer Prize. In 2014, contemporary artist Kara Walker was praised for her large-scale installation at the site of Brooklyn’s old Domino Sugar factory, A Subtlety, or The Marvelous Sugar Baby. In The New Yorker, Walker’s seventy-five-foot-wide, nude, sugar-coated sphinx was “triumphant.”

Stinchcomb was scolded for using the bar as a tableau to discuss difficult subjects in black history. But the works by Marsalis and Walker, and countless others, also interpret historical pain. That pain, while not wholly defining, is integral to the multigenerational black experience in America. We grapple with it because it’s alive, right now.

Weeks after the buzz quieted, Stinchcomb was in the alley behind Saint Leo when a thirtysomething black man rolled up on his bicycle. He wanted to bum a cigarette; Stinchcomb found him one. The man asked if he was that bartender. He’d never been to the restaurant, but had heard of the ordeal. He asked Stinchcomb why he’d write a “fucked-up-ass menu” and said that he was boycotting the restaurant because of their insensitivity. Stinchcomb retrieved the old cocktail menu and walked the man through it. The man was attentive. “Is this a fucked-up-ass menu?” Stinchcomb asked.

“I don’t know. It’s still kind of fucked up though,” the man replied.

“Our history always has been,” Stinchcomb said.

Stinchcomb invited the bicyclist to come see him sometime—at the bar. He said to him, “You can’t boycott a place you’ve never been.”

Osayi Endolyn’s writing explores food, culture and identity. Her work appears in the Oxford American, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and Eater.